Which contractors are joining the HVO revolution?

07 September 2021

As pressure mounts from governments and consumers around the world to reduce carbon, contractors are switching from diesel to hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO), an oil produced from chip fat and other waste oils, to power their equipment. Lucy Barnard finds out how.

It’s a sunny morning in Alfreton, a town in Derbyshire in the UK, but staff at demolition contractor Cawarden are feeling nervous.

Cawarden takes delivery of its first HVO fuel consignment

Cawarden takes delivery of its first HVO fuel consignment

At last, to everyone’s relief, a white fuel tanker pulls into the parking lot and pulls up alongside a Cawarden-branded Komatsu excavator – the green fuel delivery has arrived.

“Fuel deliveries are always a problem,” says William Crooks, Cawarden founder and managing director. “For green fuel there is always more of a lead time than the normal diesel. Because everyone is so busy, it’s sometimes more than a week in advance to get a delivery. We can’t just go to the local McDonalds.”

Cawarden may not be getting its fuel from the local branch of Burger King, but it is one of a plethora of contractors attempting to reduce their carbon footprints by switching from using diesel to power their machinery to hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO), an oil produced from, amongst other things, used vegetable oil from cafes and restaurants.

As president of the UK’s trade association for the demolition sector, the National Federation of Demolition Contractors, Crooks has signed the Derbyshire-based contractor up to a pledge agreed by all 140 NFDC members to switch the fuel in their machines from diesel to HVO, which can be substituted for traditional diesel.

So far Cawarden is trialling the oil on six Komatsu excavators but, when it starts using it on all 28 of its machines as well as the ones on hire, the contractor estimates it will be able to save 1,139.37 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide a year – the equivalent of 200 flights to Sydney, Australia - on the 491,000 litres it consumes annually, albeit at a price premium.

What other companies are making a change?

“Like everyone we want to do our bit for the environment,” says Crooks. “If that means it ends up costing Cawarden a bit of money, well, it’s not the end of the world compared with, well… the end of the world.”

And it’s not just Cawarden and other demolition contractors who are making the change either. Prompted by government rule changes and pressure from customers, dozens of big building companies, especially in the UK, Europe and California, are phasing out the use of diesel in their fleets and moving to the second-generation biofuel.

The UK is currently seeing some of the biggest headlines in construction ahead of a government rule change planned for April 2022 which will remove the oil subsidies currently enjoyed by users of off-highway construction machinery (see box).

So far major construction companies including Skanska, Lendlease, BAM and Sisk have all agreed to switch to HVO for at least some of their operations while dozens more are currently trialling it.

Rye Group gets its first green fuel delivery - photo courtesy of Rye Group

Rye Group gets its first green fuel delivery - photo courtesy of Rye Group

Equipment manufacturers too have hurried to show off their green credentials by ensuring that their machines are compatible with the new diesel alternative and to use the stuff in their own operations.

Provided the oil meets certain industry standards, JCB has said that machines with its stage V engines will be compatible with HVO. Mammoet is trialling it for use in its cranes and platform vehicles.

Volvo Construction Equipment has not only approved all of its machines to run on HVO, but also begun to use renewable biodiesel in its demonstration units at the firm’s customer centre in Eskilstuna, Sweden.

German crane manufacturer Liebherr-Werk Ehingen has announced that all of its engines up to 560kw had been approved for operation with HVO while the company itself will in future power its mobile and crawler cranes exclusively using the oil, consuming around 2.5 million litres at its plant in Rostock on the Baltic coast alone.

Rental companies get HVO compatible

In order to cater to a growing demand, equipment rental companies have been hurrying to reassure customers that their fleets are also HVO compatible. Speedy’s powered access division is now using HVO fuel as standard. GAP Hire Solutions spent two years trialling the firm’s fleet with the fuel to confirm its suitability and even pump rental and sales company Selwood has said that its pumps can be run on HVO.

All of this of course is good news for the oil companies supplying HVO.

New Era Fuels, which specialises in providing oil for industrial use says demand for its Green D+ HVO oil has gone through the roof already this year.

“We have seen a huge increase in demand over the last six months – over 500%,” says James Hunt, managing director for New Era. “We have over 6,000 customers with a large percentage of them in the construction industry. With many committing to the transition from fossil fuel to Green D + HVO, we have seen a huge uptake in the product from the beginning of the year to present.”

The company is encouraging customers to fix 12 month contracts for next year so that they can continue to get hold of the oil because it expects demand to outstrip supply. However, it adds that it has access to more than 15 million litres of HVO in its depots and has access to even more through its importer partnerships.

3.2 million tons

To cope with snowballing demand, Finnish company Neste, the world’s largest producer of renewable diesel, says it is increasing annual capacity to 4.5 million tons by 2023 by expanding production at its Singapore refinery. The company currently produces 3.2 million tons of renewable products every year.

Lillemor Eriksson, Neste’s communications manager says the company’s distributors are predicting “significant growth” over the coming months.

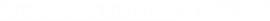

Spiralling global demand for HVO is pushing up prices for used cooking oil (UCO) and other oils used in its production. Spot prices on the main UCO trading index in Rotterdam have increased steadily to around €1,410 per metric tonne in August 2021 from €1,080 in January and a low of €760 in March (see graph)

Used Cooking Oil Methyl Ester trading prices FOB Rotterdam. Source: Greenea

Used Cooking Oil Methyl Ester trading prices FOB Rotterdam. Source: Greenea

With demand increasing so dramatically, some contractors are worried that, having made the switch to greener fuels, they could find it getting even more difficult and expensive to get fuel.

“There are some concerns, especially among smaller contractors about future supply and cost,” says Ben Griffiths, operations director at Rye Group, a demolition contractor based in Flitwick, Bedfordshire in the UK which started using HVO fuel in August on one of its sites in Harrow.

Dr Ulrich Hamme, managing director design and development at Liebherr in Ehingen, agrees. “To make HVO or other synthetic fuels attractive for crane operators, they must be available nationwide and in plentiful quantities at filling stations, as is the case today with diesel. That will not be possible from one day to the next,” he says. “But Liebherr is making a start, and we are hopeful that it will have a signal effect.”

“At the moment, we see an increasing number of suppliers, varying between different markets. The number of buyers is also increasing significantly. This is a nice development for the environment as a whole,” he added. “Unfortunately, we cannot yet estimate what this will mean for availability in the long term (especially with regard to limited resources).”

Wiliam Crooks at Carwaden is concerned that if deliveries fail to arrive on time, his company could be left bearing the costs.

Could there be a shortage of HVO?

“It would definitely slow projects down,” he says. “It’s not just our 28 machines of our own, we’ve probably got another 28 machines on our sites on hire and we have to supply all the fuel for them. So if you have 10 machines standing idle it’s pretty expensive.”

He estimates that on his fleet of vehicles which uses 490,000 litres of diesel a year, the costs of switching to HVO are likely to amount to between £5,000 and £50,000 depending on the amount of tax levied and the costs of the fuel.

Green oil: picture courtesy of Sergio Russo via Flickr

Green oil: picture courtesy of Sergio Russo via Flickr

“We estimate HVO is anything between two and 12% more expensive than red diesel,” he says. “It depends who you’re buying it off and where you’re getting it delivered to. Some of the bigger contractors can put in bulk orders, get it delivered to the yard and ship it to themselves on site. They can get it cheaper than someone like ourselves who buys it to each site around the country because we haven’t got the facilities to store or get it delivered ourselves.”

But Hunt says that HVO prices are less volatile than diesel. “HVO fluctuates but not to the level of fossil fuel,” he says. “The main causes of fluctuating are the refinery costs and new shipments of the HVO coming to the UK. We can hedge/fix prices for our customers under contract.”

He says consumers are able to buy HVO over the counter in 20 litre containers and to get next day delivery of barrels holding up to 1,000 litres.

Crooks says that although some manufacturers are currently saying that machines run using HVO could have lower capacity, he expects this to change quickly as more companies switch to the greener fuel.

Ultimately though, he predicts that as green technology improves, contractors will move away from oil-based fuels entirely.

Hydrogen as an alternative

Already a whole host of manufacturers including Hyundai Construction Equipment, Caterpillar and JCB have begun to develop hydrogen powered construction equipment. However, the technology is still in its infancy and the machines are still at the prototype stage.

Electrical vehicles currently provide a more practical alternative. JCB, Bobcat, and Hyundai are producing battery powered mini excavators – or mini excavators which can be bought with electro hydraulic units. Many more are producing electric wheeled loaders and telescopic handlers. Crane manufacturers such as Spierings are even producing hybrid electric cranes.

Hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) is a biofuel with a chemical structure almost identical to regular fossil diesel which means it can be used as a “drop-in” substitute to power conventional auto engines without being blended with diesel derived from crude oil.

Unlike first generation bio-fuels which are made from crops such as rapeseed and soy, HVO is a second generation biofuel which means it is made from pre-existing bio-waste products, primarily used cooking oil and animal fats from food industry waste. Third generation biofuels made from algae are currently in their infancy.

The oil which goes into HVO can be made from animal fat from food industry waste, fish fat from fish processing waste, residues from vegetable oil processing, used cooking oil, technical corn oil (a by-product of distilling), tall oil pitch (a by-product of wood pulp manufacturer), palm oil, tallow from beef or mutton fat and palm oil mill effluent (POME).

Oil suppliers say HVO generates up to 90% less greenhouse gas and emissions, reduces nitrogen oxide levels by up to 30% and reduces the amount of particulate matter by up to 86%.

Finish oil giant Neste is the world’s biggest manufacturer of HVO, producing more than 1 billion gallons a year. It says it uses 10 different waste products to produce its products which allows it flexibility depending on availability and price.

At the moment, the manufacturer also includes conventional oils such as palm rapeseed and soybean oil in its HVO. However, it pledged to phase this out and use 100% waste and residues in its products by 2025. The oils are imported to Neste’s specialised refineries in Finland, Rotterdam and Singapore.

This is then treated with hydrogen to remove oxygen and create diesel. However, according to environmental campaigners, the rise in demand for HVO may in fact be inadvertently contributing to deforestation.

Lobby group Transport & Environment argues that the surge in demand means that countries such as China, Indonesia and Malaysia which traditionally use used cooking oil to feed animals now find it more cost effective to export their used cooking oil to Europe and the US while feeding livestock with virgin palm oil. It adds that because the oils are mixed in bulk for transport no testing is carried out, leaving the system open to fraud.

However, fuel supplier James Hunt says that there are robust certification schemes in place and his company principally sources its oil from Europe and America.

The raw materials included in HVO - picture courtesy of Neste

The raw materials included in HVO - picture courtesy of Neste

However, although the cost of these batteries is likely to reduce in the near future, at present they tend to carry a much higher price tag than their diesel alternatives and they are not always suitable for all types of work.

“We’ve looked at machines like a Komatsu excavator which recharges the battery as it slews,” Crooks says. “So as the machine slews round that works like a generator to recharge the battery onto the machine and then at times you can then run that machine off the battery that it has produced its cell. But its £30,000 more than the same version which runs on diesel and if you don’t do a lot of slewing which we don’t normally do in demolition, it would probably be sat there using less than 90 degrees angle, you won’t generate enough power to get the hybrid working properly.”

The current problem, Crooks says, is that building sites do not have anywhere to charge electric machines and, even if they did, current electric batteries are not powerful enough to be used in the heaviest machines.

“The problem is that the first thing you do with a demolition site is to cut all the power off for health and safety,” he adds. “It’s very difficult to square that and to persuade clients to pay for that infrastructure because it will add to the build cost. That’s something that needs to happen in the future, but I can see it happening within the next ten years on major projects.”

Electric options

“I can see the fuel being more of a temporary fix but in the long term I think electricity will be a better solution. It seems to be less damaging to the climate in the way they produce it now from turbines and solar,” he adds. “These alternative fuels aren’t the saviour,”

Neste’s Porvoo refinery - photo courtesy of Neste

Neste’s Porvoo refinery - photo courtesy of Neste

But fellow demolition contractor Richard Dolman, director of AR Demolition, which is also currently transitioning to HVO fuel is sceptical.

“Given the significant environmental benefits of HVO and the likely future reductions in costs, we expect our new set up to last for several years at least. Indeed, it is hard to imagine alternatives such as hydrogen or propane will make significant progress outside light vehicle usage for some time yet,” he says.

“I am cautious about the roll-out of electric vehicles,” he adds. “There seems to be little consideration given to the environmental and financial costs of batteries ending their lives, never mind the infrastructure and energy needed for nationwide charging, the metals and materials required, and so on. As with many so-called sustainable initiatives, we need to be looking at the full picture and planning decades in advance, rather than considering the immediate term only.”

Canada: In April, the Canadian government increased its carbon tax on fuel to C$40 per tonne of industrial greenhouse gas emissions as part of a wider plan to increase its levy to C$170 per tonne in 2030.

US: California, Washington State and a group of states in New England and the Mid Atlantic have all introduced carbon pricing legislation in order to reduce carbon emissions.

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.